Rough Ride to Ngäbe-Buglé

I'm counting the seconds between flash and thunder with my eyes closed. Every five seconds is a mile.

It starts raining, harder and harder, and within a minute, I won't be able to hear thunder unless it is very close.

Reluctantly, I open a heavy eyelid to check the time.

It's 2am. What does it matter? We are so tired and sleepy, the thunderstorm hardly bothers us. Aside from unplugging electrical devices, which we'd already done, there is nothing we can do about lightning.

We're at anchor, nestled in a small bay stretching into a jungle valley. A half inch of rain was forecast tonight, and as hard as it's been coming down, I'm positive the buckets Shawn set out are already overflowing.

We arrived earlier this afternoon in the Bocas del Toro archipelago. It had been a challenging journey with a couple rest stops along the way

Bocas del Toro translates to “mouths of the bull”, though the origin of the name is unknown. Some say, the many bays are the “mouths”, other say a native leader when the Spanish arrived was named Bokotoro. Technically, we are still in the Ngäbe-Buglé comarca (district).

A few weeks ago, we were gliding into our sixth month in the idyllic San Blas islands. Comfortable in the routines we'd settled into, we'd begun discussing the upcoming change in seasons and our options. Around May, the dry season comes to an end - thunderstorms rule until November.

We’d read, been told, and seen that the Bocas del Toro area receives substantially less lightning than the rest of Panama’s Caribbean coast.

With every Caribbean sailor we'd met over the past year, we'd ask if they'd been to Bocas, having it in mind as an option for 2025 rainy season.

Some told us that they loved Bocas so much, they'd considered buying property and retiring from the sailing life there. Some they said they used to go every year until they grew weary of the difficult passage. Others painted less flattering pictures.

When asked for details about the negatives, they talked about “Bocas Town”, often called that because it has the same name as the province. We shrugged most of that off.

Some mentioned crimes against sailboat cruisers like us, with dinghies or outboard motors stolen, though some suspect the thieves may have been unscrupulous sailors, not locals. All were crimes of opportunity. In some places, the carelessness of leaving an outboard unlocked, a dinghy floating in the water, or a propane tank left on deck will not go unpunished.

We keep everything locked down, a habit we started in the US, were the waters from Portland to San Diego are fair game for shady lunatics, drug addicts, and thieves. We lock up even when there are better targets nearby, like catamarans and 50-foot sailboats, though we assume no thieves would take notice of Miette, our relatively small, old, and unassuming boat (she turns 35 this month).

Spending another rainy season at the Turtle Cay Marina crossed my mind, but only for a moment. As beautiful as the surrounding jungle was, the isolation there had grown disheartening. It wasn’t so much the lack of social interaction, since we did find a small community with the other sailors there, but that any trip into a city for supplies or a change of scenery was hours away and prohibitively expensive. We had to be content with the weekly deliveries available from one grocery store in the city, and sporadic visits by a fruit and veggie truck.

We decided on Bocas, 230 miles due west, and planned on departing San Blas while the trade-winds held steady, and preferably near a full moon. Sailing through the night, on big seas, without a visible horizon, is something we endure, not enjoy.

The lunar calendar showed our options as the middle week of April, or the middle week of May. Waiting for May seemed to come with a higher probability of unstable weather, so we set sights for April.

There are the goodbyes that are a sad staple of the sailing life.

On our last night, we were invited by Suzanne, a German solo sailor in her 70s, and Susan, a solo sailor in her 80s, for a fondue party. Shawn, Susan, and Suzanne had been meeting up for daily snorkels, or when the weather was bad, dice games.

As we nibbled the afternoon away aboard Chautauqua, a dinghy approached Suzanne's boat. She spoke German to one of them, welcoming them aboard. The husband was French and the wife German (the couple spoke to each other in French).

The woman asked us the name of our boat. Miette.

"Miette?" She asked, "like a..." She trailed off, searching for a word, but holding her thumb and forefinger an inch apart.

"Like a morsel?" she asked.

I smiled. "Yes, a little morsel or crumb. She’s a little boat, only 11 meters." Her English was limited so I left explanation at that.

She smiled. "Well, that's not so little! Our boat is also 11 meters.” They'd sailed from France in 2021 and had been cruising around the eastern Caribbean.

I knew Shawn was sad to be parting ways with Susan, after they’d spent so much time together, but they were both all smiles.

When the party wound-down, Shawn asked Susan for a hug. Susan grumbled, "Oh, I don't usually do physical contact but I guess I'll make an exception for you".

We motored our dinghy in the dark back to Miette, and then lingered for a while on deck, taking in the stars and the fresh night breeze, knowing we’d miss this wonderful corner of the world.

Weighing anchor after another rosy orange dawn in San Blas, we motored away from the reef that had protected us, raised the mainsail, the staysail, and finally the headsail. We shut down the engine, turned on course, and trimmed the sails.

A pod of small dolphins gave us an escort for a few minutes, playing at our bow, crossing in front of Miette like daredevils. Superstitious sailors believe dolphins to be a good omen.

The winds were 15 knots on the beam, right in Miette’s sweet spot. We rocketed out of the islands at 7 knots, slicing through the beautiful blue water. With the engine off and sails trimmed, Miette raced onwards, well-balanced and needing only a light hand on the wheel. By noon, the San Blas islands were disappearing behind us.

After night fell, we were passing the town of Portabelo. I realized I had cell reception and pulled up the weather (we had taken the Starlink dish down). The weather was changing, and not in our favor. I checked four different forecast models and they all agreed on bad news.

Shawn was on watch, so I went out to the cockpit to brief her.

"Hey, I just got a weather update. There’s a big low setting up ahead of us - it looks big and it might get nasty. It’s going to give us strong headwinds and maybe thunderstorms. I'm leaning towards heading into the Shelter Bay anchorage to wait for better weather. We could be there by 1am and we have plenty of moonlight to see. I don't see decent weather in the forecast for the next 4 or 5 days."

"Ok, that's fine". That’s as neutral as an answer as you can get, but after 4 years of sailboard cruising, it’s best to keep hopes and disappointments in check, and just roll with the changes.

We made the course change and immediately had a better angle to the wind. The sails filled once again.

When it was time for me to stand watch, I sat at the helm, bracing myself against the big waves rocking us, watching the lights of ships to starboard and the shore to port.

Miette settled into a rhythm as sea-miles slowly unreeled behind us. I was halfway zoned out listening to a podcast when a dolphin jumped entirely out of the water, just a few feet away. I jerked, thinking something big was jumping into the cockpit. It had taken a half second to register what I'd seen - it startled me enough to get adrenaline flowing. It's not uncommon for us to see dolphins, but we don't usually see them jump all the way out of the water like that, and certainly not that close to us. I’ll bet it had a good laugh at the look on my face. If you’ve ever spent even a little time around dolphins, you know they have fun.

Within a couple hours, we were in the high-traffic zone approaching the Panama Canal, so both of us were on deck and alert.

As a safety precaution, we started the engine two miles before reaching the cut in the massive breakwater into Bahía Limón. The water there is never happy, churning unpredictably, slamming into the breakwater and bouncing back, waves thrashing into yet more waves. Cargo ships leaving the Panama Canal charge full speed out to sea through a gap in the breakwater just big enough for one ship. They could easily mow us down and not even notice.

The shipping terminals at the ports of Colón light up the sky in harsh white and sodium orange, and the bright moonlight paints the black sea’s horizon with a silvery shimmer. Panama City is only 50 miles to the south, and the clouds over it also glow. Giant ships at anchor are brightly lit. One looks like a floating refinery, all tanks and tubes. We haven’t seen the modern world in a half year, and a strange bit of nervousness forms in my stomach, as if knowing the first day of school is coming after a long summer break, or the Sunday night before starting a new job.

In the distance, the green and red channel markers and breakwater entrance lights appear to rise as we get closer. "Red Right Returning" is the mnemonic to keep the red lights to your right when returning from sea.

A quarter mile from the entrance, just as it starts to rain, we get an "imminent collision" warning from our AIS system, which receives position and speed data broadcast from ships and compares it to our own. A ship leaving the canal is headed out to sea through the cut we are sailing towards, but I can’t make it out in the darkness and rain.

I turn to port for a minute and reduce throttle, the sails suddenly confused, the boom pulling against the preventer line, making a racket. Shawn sees the ship first and calls it out. It had been passing behind an enormous tanker anchored bear the breakwater. The rain didn't help visibility either. The departing ship is a small freighter, maybe only 300 ft long, and moving fast.

We pause a minute, until sure we will pass behind it. It glides in front of us at a safe distance, and we resume our approach to the entrance.

The wild ride at the entrance doesn't surprise us. This will be our sixth time through. Once behind the breakwater, the bay is relatively flat and a welcome calm.

By the time we've dropped the sails and set the anchor, it's 2am. Shawn is fast asleep while I keep one eye open, watching our position, eventually falling asleep around 4am. We had sailed 85 miles in 14 hours - record speeds for Miette.

The following night, we dinghy into the marina to see our friends Myles and Barb and to treat them to dinner. Shawn and I are wearing sandals, the first footwear we’ve worn in months, getting our land-legs back.

The last time we saw our Canadian friends, we’d escorted them to Shelter Bay after they had a massive fire onboard and needed a place to work on restoring their boat. While we were enjoying the San Blas islands, they were living on a borrowed motor yacht, gutting Blue Horizon and wrestling with their insurance company. Blue Horizon, which is an Island Packet yacht like ours - only substantially bigger - was a total write off.

They are in the process of buying their boat back from the insurance company and waiting for the claim to pay out - funds they’ll use to restore the boat. They’ve been waiting for 5 or 6 months, paying for everything out-of-pocket in the meantime, in hopes the insurance doesn’t screw them over. They’re in their mid-60s, and the boat is their only home, so going back to work or living with their grown children aren’t options they want to consider.

To be clear: they aren’t paying workers to do the restoration - they’re doing it themselves. Myles is one of those people who can figure out almost anything and master it (as long as it doesn’t involve computers or iPhones). He built the log cabin their children grew up in, drove locomotives, cranes, tractors, front-loaders, and even raced dirt-bikes. I’m sure I’ve written about him before, but he’s the cool, capable uncle I never had. While Myles tackles the electrical, woodwork, and other challenges, Barb is fabricating all new upholstery for their boat - all of it looks flawless and professional. What they’d had before was severely smoke damaged or burned.

Before dinner, they took us aboard to show us the restoration progress. The smell of smoke was gone. Wires hung out of empty fixtures, wood paneling and gel coat had been removed, the teak and holly floors were covered with protective plastic, and the new electrical panel was halfway wired (he’d finish it a couple days later, sending me photos of the 25-hour job).

Six days passed before another window of opportunity opened up, this time my remote work being a bigger constraint than weather.

Shelter Bay is not a pleasant anchorage by any stretch. While there are periods of calm, every now and then we get rocked hard by a set of big waves that have made it into the harbor. For the past 5 months, the only man-made objects anywhere in sight were the sailboats at anchor near us.

There is a marina around the corner, but it’s expensive, so we stubbornly stayed out at anchor. Some sailors call the marina “Shelter Pay” because they nickel and dime sailors for every little thing, and have a monopoly for any sailboats waiting to pass south through the canal to the Pacific.

When the time came, we were eager to get out of the anchorage, even though we knew the 6 day delay meant that, even with an early morning departure, we'd have 3 hours of sailing in total darkness after nightfall until moonrise.

We got up just before 6am, had coffee and breakfast, and started the engine. As the anchor chain came up a little stretch at a time, Shawn had been throwing a bucket overboard to wash and brush the mud and clay off the chain. When I next pressed the button to raise more chain, nothing happened. The rope, which Shawn had tied to retrieve the bucket, had gotten caught in the windlass, the machine which brings chain up or down out of the chain locker. I put Miette in idle, pointed us into the swell, set the auto-pilot to hold course, and grabbed tools. I had to partially disassemble the windlass, covered in stinky, sticky mud, to work the chain and tangled rope free, while keeping an eye on where we were drifting, since we were surrounded by ships at anchor. Twice, I had to run back to the cockpit to change course, punching in 10-degree increments with my mud-free knuckles.

By 8:15 am, we had the anchor up. I waved at a man in a hard-hat, who had been watching us from high on a ship, probably wondering what the hell we were doing.

“Ok, before we get our asses kicked out there, let’s wash up, change clothes, take some deep breaths, and reset. Let’s move slow and think about what we’re doing. No more stupid mistakes, ok?”

Shawn had no problem with my suggestion, though I apologized for calling the mistake stupid. She had been up on the bowsprit scrubbing the mud off the chain, like she’s done a hundred times before, while I was pushing a button in the cockpit. Nobody needs to tell me who has the harder job.

Getting out of the breakwater was an ordeal again, but this time, the wind was against us, instead of pushing us through. Short, choppy seas slowed our forward momentum, sometimes completely stopping our forward progress, while the rocks of the breakwater looming dangerously close. To make it even more stressful, a massive inbound ship was headed towards us. Miette felt comically small and weak in these conditions. The next harrowing 15 minutes felt like an hour.

Luckily, ships approaching from sea are slowing down, so we slipped through and made a hard turn to port as soon as we were safely clear of the breakwater while the inbound ship was still a mile away. I had been half-expecting the dreaded 5 horn blasts from the freighter signaling get out of the way! The wind suddenly filled the sails. Miette heeled 10 degrees to port and quickly sped away, 140 nautical miles to go.

We sailed for most of the day, but started the engine in the late afternoon to keep our ETA reasonable when the winds weakened and our forward speed slowed to a crawl. Having studied the forecast, I knew we didn’t have days to bob around waiting for winds. Another big low-pressure system in the Gulf of Panama was slowly growing and working it’s way north towards us. Some sailors have a vastly higher tolerance for bobbing around in misery before they’ll start the engine (I’m looking at you, John Matherly) but once we’re down a crawl and nasty weather is coming, I have no problem motoring away.

For the most part, the seas stayed around 7-8 ft from behind, on our starboard quarter. Whatever the seas are, every now and then you get a set of much bigger waves that have piled on one another. Looking up at their crests, it can feel like they're going to go over us, but instead, we’re carried up and lowered down. It feels like being on a giant teeter-totter. Our GPS speed swings through these waves from 8 knots one moment, 2 knots the next.

Our night watches are uneventful, though 5 minutes can feel an hour. We do our best to sleep when we each have our turn below. When we swap, the exchange is brief: “nothing to report”. No ships, no fishing boats. No whales, mermaids, or shooting stars, and no sight of shore. Nothing to talk about, just an eagerness to get below, get horizontal, and get some rest.

The winds begin to shift against us during my 3-5am watch. Shawn had furled the headsail and sheeted-in the staysail and mainsail so they weren't creating drag or taking wear. Miette's GPS speed drops to less than walking speed. We have 50 miles left, but at this rate, the navigation system calculates a disheartening number of hours - actually days.

Sailing is almost never about pointing directly towards your destination, but we'd been lucky for a couple days, and now that was over.

By 7am, it’s clear that we need to tack. Shawn is exhausted and cranky, trying to rest down below. The motion and sound of sailing big seas make sleep difficult. The charts show an uninhabited island 15 miles away, and we could possibly take a rest there. Isla Escudo de Veraguas, or “Shield of Veraguas Island” is said to be worth a stop, weather permitting. Veraguas is the former name of the province we’re near, and possibly, the name Panama had before the Spanish arrived.

I turn us toward the island, and will inform Shawn after she gets some sleep. Immediately, we have a better angle on the wind and our speed picks up.

Just as the sun rises and Miette again finds her rhythm over the waves, I smell earth and dirt, and minutes later, spot the island. As tired as I am, the sight of land is reinvigorating. We make the 12 miles in about 3 hours.

Getting around the island proves to be intense. The massive swells we'd been riding suddenly meet a sharp rise in the sea floor. The swell becomes huge rollers, some of them breaking. All that's missing from the scene are people riding surfboards out there.

I steer away from the worst of them, but in one moment, Shawn and I look behind us, and then look up, to see a wave rising behind us. To be standing at the helm, and looking up at the top of a wave, is unnerving. Even if the wave is only 8 or 10 ft, with the boat’s stern pointed downward in the trough of the previous wave, the apparent height of the next one is exaggerated. Wind is blowing the crest of the wave off, and I wonder if we are about to get clobbered. We exchange an "oh shit" look and brace ourselves.

Instead, the stern is swiftly lifted up like a toy, the bow pointing steeply down. We surf for a few seconds, surging forward, then slow as we slide up and over as the wave overtakes us. As the monster wave crest passes Miette, the stern drops into the trough behind us and the bow points skyward. For a moment, it feels like we are going backwards. The forces on the rudder are strong and I'm white-knuckled to keep us perpendicular to the waves. Getting turned sideways by waves of that size will lead to a knock-down at best, or capsize at worst.

"Keep a look out behind us!" I shout over the wind and waves. The sonar is showing 15 ft of depth - no wonder these waves are rising so high - we were in thousands of feet of water just a while ago. We should have stayed further out from the island. When there is less force on the rudder, I try to grab a video clip.

Shawn looks at me, annoyed. "Stop filming!"

She's right, and besides, by the time the camera boots up and starts recording, the next waves are far less dramatic. The video clip I manage to record utterly fails to capture the experience.

Behind the island, we get a breather, and calm ourselves before finding a spot to anchor.

The afternoon is sunny and calm. We swim, eat lunch, take naps, and even fly the drone.

We would not make it to shore at Escudo de Veraguas. That night, the winds and swell shifted, leaving us completely unprotected. Miette rocked and rolled all night, rain pounded her cabin, and her old bones creaked while we tried our best to sleep. Ear plugs helped, but as with every first night at anchor somewhere, I only doze - periodically checking our position to make sure we aren’t dragging.

There isn’t much color to the dawn sky, a low overcast sapped most of the blue from the sea. We had breakfast and got under way. We raised two sails, mostly for stability, and for a couple hours, had help from the wind before it turned against us.

”I’m ready for this passage to be over,” I tell Shawn. She nods and climbs down the companionway to get her rest below. We’re often asked if we get sea-sick. When you’re at the helm looking at the horizon, or down below and laying down, the motion doesn’t bother us. The times we’ve gotten “green in the gills” have been when preparing a meal, troubleshooting an engine problem, or night sailing without a visible horizon.

It rained for an hour on my watch, a heavy curtain of cold, fat drops. My sailing jacket is at least a dozen years old and has lost much of its water resistance. I'm cold and clammy under it. My swim shorts are soaked and my fingers and toes are pruned. I'm actually cold - a rare sensation in the tropics. Try to enjoy feeling cold! I tell myself. It’s useless - this sucks.

The skies clear around noon, and we give a wide berth to rocks off the Pico Valiente peninsula we're approaching. Over a slow half hour, our course is a wide U-turn into a bay set into the tip of the peninsula.

Once inside the bay, Laguna Bluefield, the water is flat and the winds a gentle breeze. The name comes from a 17th century Dutch pirate, Blauvelt, who used this bay.

Jungle rises from the water up to lush green hills. Settlements dot some of the shoreline. Many are just a corrugated metal roof on a wooden frame. Some have walls with empty rectangles as windows, and in others, just the beams holding the roof over hammocks. We don't see anyone ashore, but could hear chickens and dogs. Around one uninhabited point we hear toucans.

Once we notice people in canoes, they seem to be all over the bay, going about their way. Entire families out there paddling from one place to another.

The sonar is not fully in agreement with depths on the chart, so we proceed slowly, looking for a place to anchor. In addition to having studied the charts and the cruising guide, I had looked over satellite imagery and taken note of a sailboat anchored far back into to the bay.

After the heavy rains, silt makes the water green and murky. Shawn stands at the bow looking for rocks and sandy patches. I circle a promising spot, getting a feel for the surrounding depths, since I can’t fully trust the charts. We stop over a spot 20 ft deep, drop the anchor and let out chain as the wind blows us back.

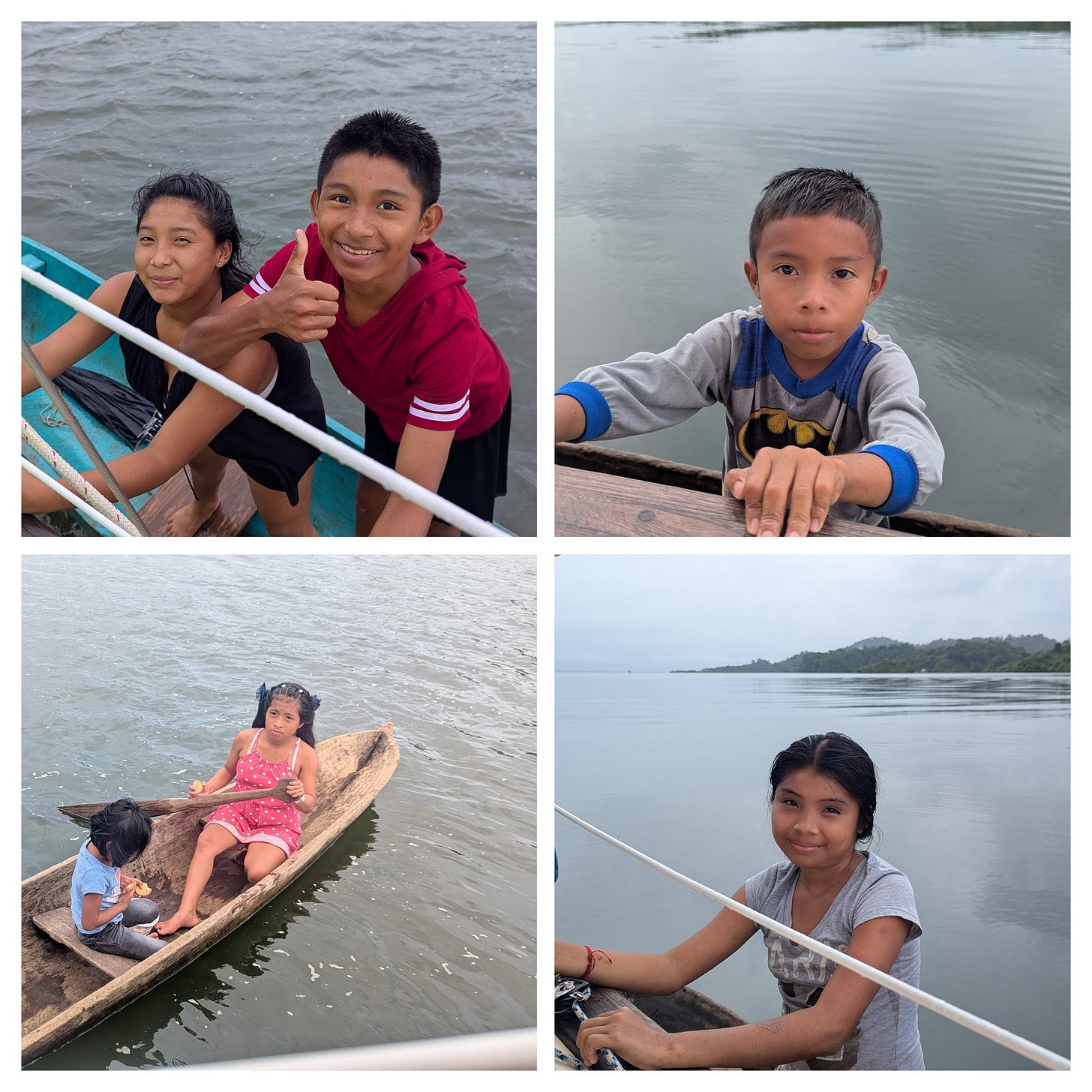

While cooking dinner, we hear a voice, and I see a little girl looking back at me. The indigenous people here of the Ngäbe tribe still speak their native language, but it turns out the girl speaks Spanish.

Marisnet is 10 years old and at first I think she has blue eyes, but in fact, they're so black, they're just reflecting the sky. We give her a cookie, which she gobbles up.

She points our her village and where she goes to school. We ask her random questions, keeping it things a 10 year old might know. She has a dog named Cola (tail), a cat named Mariposa (butterfly) and a baby chick named Pollito (chick).

An old man paddles up, and the little girl clams up. Zacharia is the serious type, asks us many questions, but his voice is raspy and he’s hard to understand. We excuse ourselves to eat our dinner, which is getting cold down in the galley.

At dusk, another old man paddles up. He introduces himself as Daniel and is very friendly and delighted that I speak Spanish. He says he comes from the other side of the peninsula and asks if we want to buy coffee. We buy two small bags of ground coffee. I notice his cargo is a dozen freshly hewn paddles, with a distinctive handle we've seen our other visitors have. He asks if we want to buy one but we have no use for it.

He smiles a lot, despite having maybe six teeth, and his eyes sparkle. He tells me how there are many Chinese people in Panama, and tickled that they always call him “Tio”. Uncle. He jokes that he never knew he had such a big family!

It rains heavily that night and throughout the day. Shawn and I both catch up on our sleep, exhausted from the long, rough days getting here.

After a few days here, when the rains let up and school is out, the cookie mob comes out. I think word about our cookies spread, so kids aged 4 to 11 paddle out for the treats.

Two girls ask for school supplies, and after tearing through storage compartments, all we have to offer are a couple notebooks with lined paper and pencils which are really for drawing, not writing. They are happy enough with those. Shawn gives a pair of shorts to another girl.

We buy hand-pressed coconut oil from the mother of a couple girls we’d met the day before, a pipa (a young coconut, with more water and less meat) from a couple boys, and a hand-sewn bag. I ask the mother, Ibet, where they get fruits and vegetables. She points to a nearby clearing and says the farm there doesn’t have much fruit right now, coconuts and sometimes pineapples. She asks what kind of veggies we want. I rattle off carrots, onions, lettuce, cucumber, tomatoes… she stops me. “They don’t have any of that.” While we talk, her 3 year old, named Kevin, is trying to climb aboard our stern arch. She warns him, “you climb aboard that boat, and you’ll be staying with them.” He giggles and she shakes her head, and calls him a monkey.

During the day, we hear toucans, parakeets, and other birds. Mixed in with that we hear an occasional chainsaw or rooster crowing near the village. At night, it’s the silence of the jungle’s insect chorus.

The bay is so tranquil one night that as we stand on the deck, the stars spread above us are mirrored in perfectly flat water. We are floating in outer space!

Next: Going ashore at a Ngäbe village

In the meantime, enjoy our narration-free video highlighting our voyage.